Are the habits that you have today, on par with the dreams you have tomorrow?

Research has been conducted and it has been found that it takes on average approximately 66 days to implant a habit of a simple task (such as eating a piece of fruit every lunchtime). With complex habits, this process takes slightly longer. The neural pathways in your brain will actually physically change (as any muscle would with exercise) during this time the nerves, synapses and myelin sheaths will all have been made stronger and faster. When looking to form a habit it is necessary to take small steps rather than big ones. So, it is wise to start small and dream big.

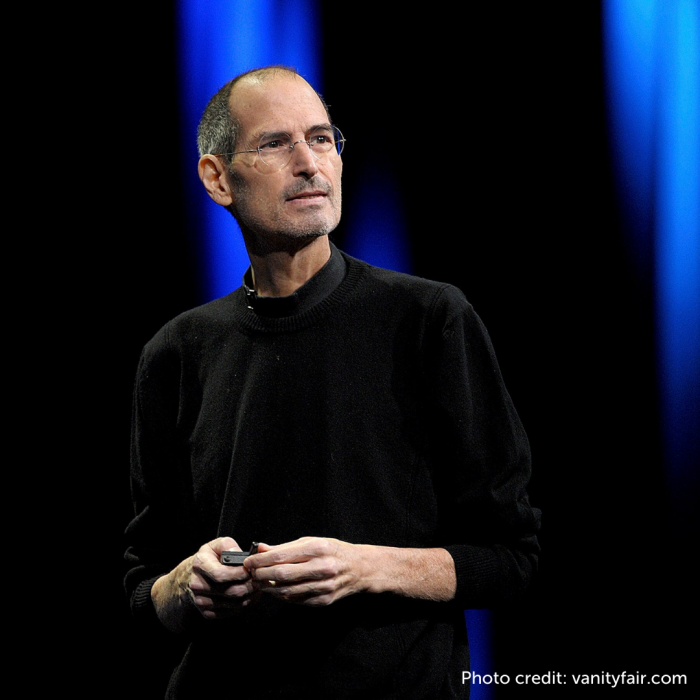

By resisting temptations but ALSO making decisions, studies have been able to prove that our willpower is a limited resource and can be depleted during a day. This is why Steve Jobs wore the same polo-neck sweater, why Barak Obama wears the same suit and Mark Zuckerberg the same T-shirt every day – to prevent decision fatigue. Implementing good habits can help prevent this phenomenon from occurring. This is why good habits are so incredibly valuable: they help us save willpower.

By resisting temptations but ALSO making decisions, studies have been able to prove that our willpower is a limited resource and can be depleted during a day. This is why Steve Jobs wore the same polo-neck sweater, why Barak Obama wears the same suit and Mark Zuckerberg the same T-shirt every day – to prevent decision fatigue. Implementing good habits can help prevent this phenomenon from occurring. This is why good habits are so incredibly valuable: they help us save willpower.

Rehearsing a new habit will take a lot of willpower in the beginning, but once this habit has taken root, you can take your hands off the decision-making steering wheel and ease your foot off the willpower accelerator. It is then reasonable to propose that the fewer small decisions you have to take in the course of your day, the more effectively you will make the important ones.

What is fascinating, and has been found in a number of studies, is that one good habit can quickly turn into several. Once you have implemented a good habit, it often acts as the soil from which other good habits grow almost automatically. In one study of college students doing a weight training program for two months, one positive habit triggered others and soon the participants started to eat healthier, reduced their alcohol and cigarette consumption, studied more for their courses and even tidied their rooms more frequently.

We don’t notice tiny changes, because their immediate impact is negligible. If you are out of shape today, and go for a 20-minute jog, you’ll still be out of shape tomorrow, and likely feel worse for it. Conversely, if you eat a family-sized pizza for dinner it won’t make you overweight overnight. But if we repeat small behaviours day after day, these choices and behaviours compound into major results. Eat pizza every day, and it’s likely you will have gained considerable weight after a year. Go jogging for 20-minutes every day and you’ll eventually be leaner and fitter, even though you won’t have noticed the change happening.

We are what we repeatedly do…Therefore excellence is a habit

If you want to make a positive change in your life, you should recognise that change requires patience, as well as confidence that your habits are keeping you on the right trajectory even if you aren’t seeing immediate results.

This can be shown in the Expectations vs Reality model found in the SquashMind app. It will be worth searching for this lesson to get a clearer understanding.

What can you do 1% better each and every day and accumulate this over time? Most players enter the court trying to get the outcome they desire. To win the match. To get the big title. But there can only ever be 1 winner. Very often it’s the player that has focussed on the daily and weekly processes in their training, behaviours, attitudes and habits who are successful at the end of the day. Again, this may not happen immediately, but over time, the player that becomes more process focussed over outcome focussed gets the results they want. This way of thinking is very closely linked to the SquashMind philosophy:

“No one ever got good by sitting and theorising over it. The real improvements come from practically applying the theory with the correct tools on a steady and consistent basis over time. You need to get your reps in!”

Habits work in the following order:

Cue > Craving > Response > Reward

Every habit is subject to the same process.

Cue

Change our environment and make it optimal, for example, we want to practise the guitar, leave the instrument in the centre of the room. Trying to eat healthier snacks? Leave them out on the counter, instead of in the salad drawer. Make your cues as obvious as possible, and you’ll be more likely to respond to them.

A second way to strengthen cues is to use implementation intentions. Most of us tend to be too vague about our intentions. We say I’m going to eat better and simply hope that will follow through. An implementation intention introduces a clear plan of action setting out when and where you’ll carry out the habits you’d like to cultivate. And research shows that it works. So, don’t just say I’ll run more often. Say “on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 2.30 pm when my reminder on my phone buzzes I’ll put on my running gear and clock 2 miles”. Also, help yourself by leaving your running shoes out where you’ll see them. Studies have shown the effectiveness of writing statements like this down and leaving them in a prominent place. You will be giving yourself both a clear plan and an obvious cue and it may surprise you how much easier this will make it to actually build a positive running habit.

Many people think they lack motivation when what they really lack is clarity

Craving

The human brain releases dopamine, a hormone that makes us feel good, when we do pleasurable things such as eating or laughing with friends over a joke. But what has been proven also is that we get a hit of feel-good dopamine when we simply ANTICIPATE those pleasurable activities. It’s the brain’s way of driving us onward and encouraging us to actually do things. So, in the brain’s reward system, desiring something is on par with getting something, which goes a long way toward explaining why kids enjoy the anticipation of Christmas so much. If we make a habit of something we look forward to, we will be much more likely to follow through and actually do it.

A great technique for this is called temptation bundling. That’s when you take a behaviour that you think of as important but unappealing and link it to a behaviour that you’re drawn to, one that will generate that motivating dopamine hit.

For example, if you need to work out, but you want to catch up on the latest A-list gossip, you could commit to only reading magazines while at the gym. If you want to watch Netflix, but you need to study for a test, promise yourself half an hour of Netflix after you have dedicated yourself to doing 1 past practice paper. Soon enough you may even find those unattractive tasks enjoyable since you’ll be anticipating a pleasing reward while carrying them out.

Response

You need to work on reducing friction for good habits but look to increase the friction for bad ones. Think about your environment. Is it primed for frictionless good habits to appear?

Use the 2-minute rule to make the new activity feel manageable. The principle is that any activity can be distilled into a habit that is doable within 2-minutes. Want to read more? Don’t commit to reading one book every week, instead, make a habit of reading 2 pages per night. Want to run a marathon, commit to simply putting on your running gear every day after work.

The 2-minute rule is a way to build easily achievable habits and those can lead you on to greater things. Once you’ve pulled on your running shoes you will probably head out for a run. Once you’ve read 2 pages you’ll likely continue. The rule recognises that simply getting started is the 1st and most important step to do something. The key is not to overreach and fall short when looking to start a new habit.

Reward

The final and most important rule for behavioural changes is to make habits satisfying.

This can be difficult, for evolutionary reasons. Today, we live in what academics call a delayed return environment. You turn up at the office today but the return, a paycheque, doesn’t come until the end of the month. You go to the gym in the morning, but you don’t lose weight overnight. So, when you are pursuing habits with a delayed return, try to attach some immediate gratification to them.

To do this, use reinforcements. More will be discussed below on this in habit tracking. But in simple terms when you reinforce the habit you are able to change your identity. You now do not try and eat healthy, but you see yourself as a healthy person, you now do not try and get fitter, but you see yourself as an athlete, you do not try and become more mindful and present, but you see yourself as a meditator. This is the deepest layer of habit formation, creating that identity change by your processes, actions, behaviours and habits.

But, however pleasurable and satisfying we make habits we may still fail to maintain them. So, let’s take a look at how we can stick to our good intentions:

Habit tracking

Habit tracking is a simple but effective technique. Many people have kept a record of their habits. One of the most well-known is founding father Benjamin Franklin. From the age of 20, Franklin kept a notebook in which he recorded his personal virtues which included aims like avoiding frivolous conversations and to always be doing something useful. He noted his success every night in his journal.

Jerry Seinfeld, the most well-paid and arguably most successful comedian of all time, speaks about his ultimate desire to not break his chain. He uses a wall calendar to mark off every day he writes a joke. He puts a cross through the day when he has written a joke and has been achieving this chain for several years. His advice goes

Jerry Seinfeld, the most well-paid and arguably most successful comedian of all time, speaks about his ultimate desire to not break his chain. He uses a wall calendar to mark off every day he writes a joke. He puts a cross through the day when he has written a joke and has been achieving this chain for several years. His advice goes

“Get a big wall calendar that has a whole year on 1 page and hang it on a prominent wall. The next step is to get a big red magic marker. For each day that I do my task of writing I get to put a big red X over that day. After a few days you’ll have a chain. Just keep at it and the chain will grow longer every day. You’ll like seeing that chain, especially when you get a few weeks under your belt. Your only job is to not break the chain.”

You’ll notice that Seinfeld didn’t say a single thing about results. It didn’t matter if he was motivated or not. It didn’t matter if he was writing a great joke or not. It didn’t matter if what he was working on would ever make it into a show. All that mattered was not breaking the chain.

You do not rise to the level of your goals, but fall to the level of your systems

In summary, a tiny change in your behaviour will not transform your life overnight. But turn that behaviour into a habit that you perform every day and it absolutely can lead to big changes. Changing your life is not about making big breakthroughs or revolutionising your entire life. Rather, it’s about building a positive system of habits that, when combined, deliver remarkable results. In the beginning, the effects are fractional, but given time, they become radical!

If you need a little extra motivation, watch this short video of basketball Hall of Famer Stephen Curry on the power and effectiveness of his habits for his career.

Jesse Engelbrecht

Sign up to the SquashSkills newsletter

Get world class coaching tips, straight to your inbox!