We get a ton of great feedback and questions sent in to us here at SquashSkills, many that well warrant a wider audience. In a new periodical feature on the blog, we’re going to be expanding on some of these discussions and making them into full articles.

This week’s then, sees us addressing a recent question that came in from a member about the use of ankle weights for the squash player:

“I was wondering if you have any advice on utilising ankle weights while playing/training? I have heard that some Egyptian players do this?”

Ankle weights usually come in the form of padded bands or pouches that have sand, water, or some kind of other weight inside, and are designed to be worn around the bottom of the shin and Achilles area. They come in a range of different resistances, most often somewhere between one and five kilograms.

The generally considered theory behind utilising ankle weights is that wearing them while ghosting and performing other movement drills on court will make them more challenging, which will then translate into faster, stronger movement when the player removes the weights.

Using weighted clothing and equipment has long been popular in many sports, with athletes using weighted balls, gloves, and bats as well as the standard wrist and ankle weights, to make their sessions harder and induce a training effect.

Using weighted clothing and equipment has long been popular in many sports, with athletes using weighted balls, gloves, and bats as well as the standard wrist and ankle weights, to make their sessions harder and induce a training effect.

There is much conjecture as to the value of these training methods however. Whilst used by some athletes and coaches, there are just as many others who claim that using weighted implements can negatively affect subsequent competitive performance – little direct research is available, but this once widespread practice in sports such as golf, baseball, and boxing is certainly not as popular as it was even just 20 years ago.

One of the main reasons that many sportspeople have moved away from the practice is due to the effects it can potentially have on technique. By taking into consideration biomechanics and force vectors, this can be more easily understood. Take boxing as an example; attempting to improve punching power with the use of hand weights makes some sense on the surface, but when you stop to consider the angle of resistance of the weight compared to the path of the punch, it quickly becomes a little murkier.

The weight is pushing down in a vertical plane, while the punch is (usually) travelling in a horizontal plane – the resistance isn’t in the right direction to resist the force behind the blow, making the movement harder certainly, but not providing the resistance necessary to increase power in the punch. Overloading an action from the wrong angle can lead to issues with technique through sub-optimal neuromuscular firing patterns, and over-compensation from other related muscle groups – potentially doing a lot more harm than good.

This would be the exact same issue with the squash player utilising ankle weights – movement and footwork patterns are going to be affected by a weight pushing down vertically on the feet, as opposed to a more suitable set-up of working against a load that’s pulling in the opposite direction and resisting movement directly (such as with resistance bands and bungee cords).

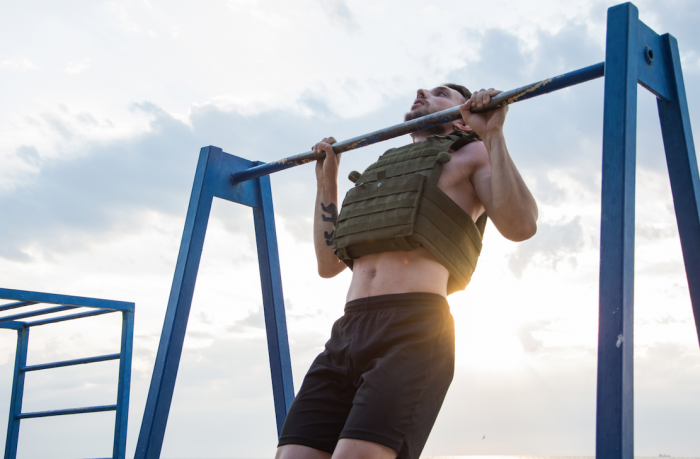

A weighted vest is one similar alternative often used, differing from ankle weights in that the weight is not directly pressing down on the extremity of a limb at the hand/foot, but attached and stabilised by the torso. Research, however, has suggested that a weighted vest really needs to be at quite a significant load to generate a training effect (around 40lb), way heavier than most people generally use – the additional danger of wearing a weight this heavy is the effect it has on the arches of the feet, potentially causing damage and instability in and around the foot/ankle region.

A weighted vest is one similar alternative often used, differing from ankle weights in that the weight is not directly pressing down on the extremity of a limb at the hand/foot, but attached and stabilised by the torso. Research, however, has suggested that a weighted vest really needs to be at quite a significant load to generate a training effect (around 40lb), way heavier than most people generally use – the additional danger of wearing a weight this heavy is the effect it has on the arches of the feet, potentially causing damage and instability in and around the foot/ankle region.

This hits on another of the issues to consider in using ankle weights: the risk of injury. While ankle weights are generally going to be far lighter than the typical weighted vest, their placement at the extremities of the leg means their effect will often be more acutely felt. Working at the velocities necessary to develop speed and power, even these significantly lighter loads will put an unnatural strain on the joints, and can be enough to distort and unbalance correct movement patterns.

This idea that many athletes have of equating ‘making something harder’ with ‘making something more effective’ is a pervasive one, but one that is not always correct. Making you wear squash shoes two sizes too small would certainly make your ghosting feel harder, but it wouldn’t make it any more effective in terms of the results you get from it. It’s similar to the training masks that restrict air intake that were briefly very popular – research showed that they certainly made training a lot tougher, but not in any way that would carry over a positive training effect.

The very best way to increase the explosiveness and efficiency of your on-court movement remains through developing a firm foundation of strength and power using a variety of weighted compound lifts and bodyweight exercises. This foundation of strength can then be built upon with high-intensity squash-specific drills on court, that closely replicate the movements you will make in a game – just like the ones we feature in our extensive exercise library here on the site.

Gary Nisbet

B.Sc.(Hons), CSCS, NSCA-CPT, Dip. FTST

SquashSkills Fitness & Performance Director

Sign up to the SquashSkills newsletter

Get world class coaching tips, straight to your inbox!