SquashSkills has teamed up with stats company Cross Court Analytics to provide a data-driven angle to the Coaches Corner game reviews. Next up, Cross Court take a look at the stats behind Game 1 of Ollie Harris vs Ollie Hudson.

Watch: Coaches Corner with Linda Elriani analysing Ollie Harris

Watch: Coaches Corner with Laurent Elriani analysing Ollie Hudson

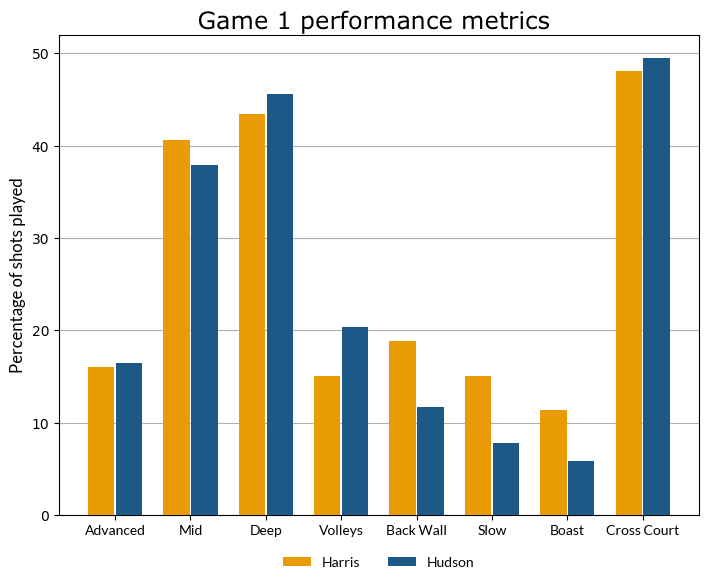

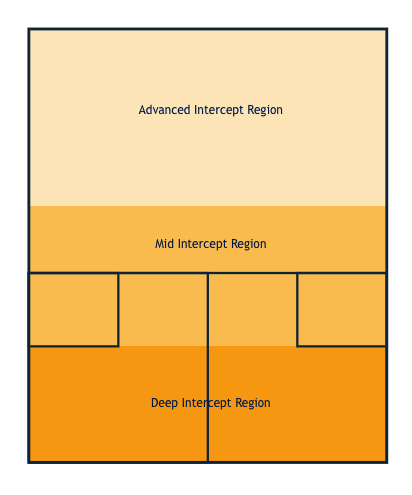

At Cross Court, the majority of the data we collect is based around shot location and shot type. A shot might be hit from deep on the backhand, cross-court, with pace taken off, and returned by the opponent with a mid-court volley boast. By mapping out matches in this way, our aim is to discover and communicate meaningful patterns of play in squash rallies. Our first step in analysing any match is to plot and compare these location and shot type performance metrics, as seen in the chart below.

In contrast to Game 1 of Potter vs Turney, in which large performance metric differences were visible at a glance, Harris and Hudson’s Game 1 is notable for the similarity of both players’ metric profiles. Both Harris and Hudson hit ~40% of shots from mid-court, and slightly more from behind the service boxes (deep). Each brought the other forward one shot out of six.

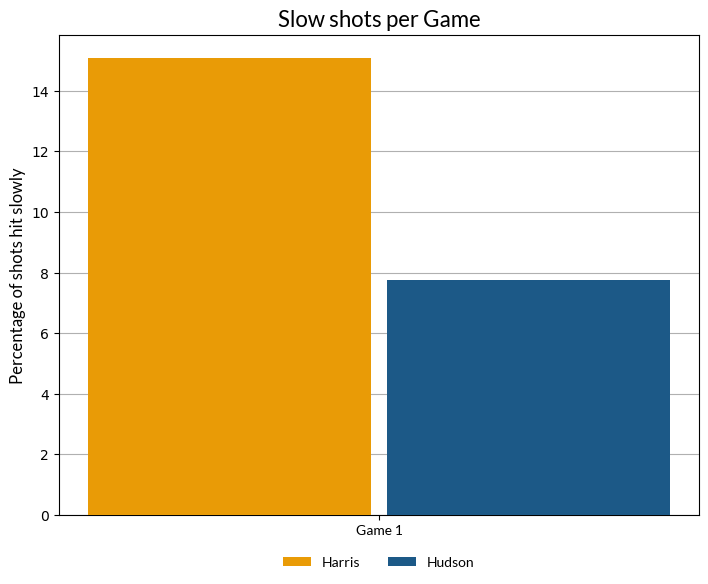

The players’ choice of shots did differ more than their shot locations: Harris, for instance, hit the ball on the rebound more frequently, and used boasts twice as often as Hudson. However, these discrepancies are not enormous, and the rarity of such shots means the differences are small in absolute terms: Harris slowed the tempo on 15 occasions; Hudson 8 times.

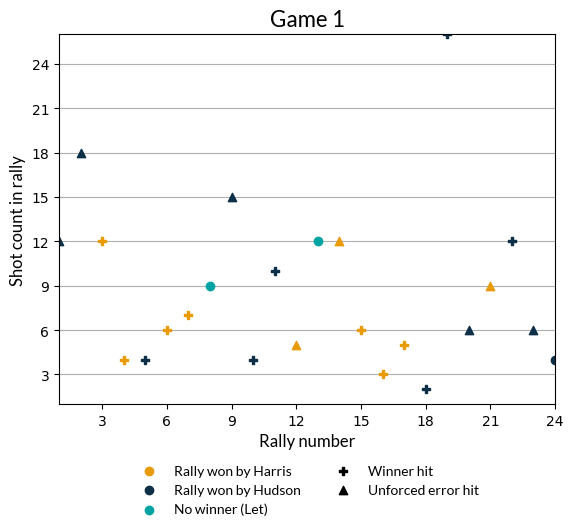

To us, the broad similarity of these metric profiles points to a Game decided not by differences in styles of play, but by fine margins: a Winner here, a Tin there. As such, let’s take a closer look at both players’ Winners and Errors.

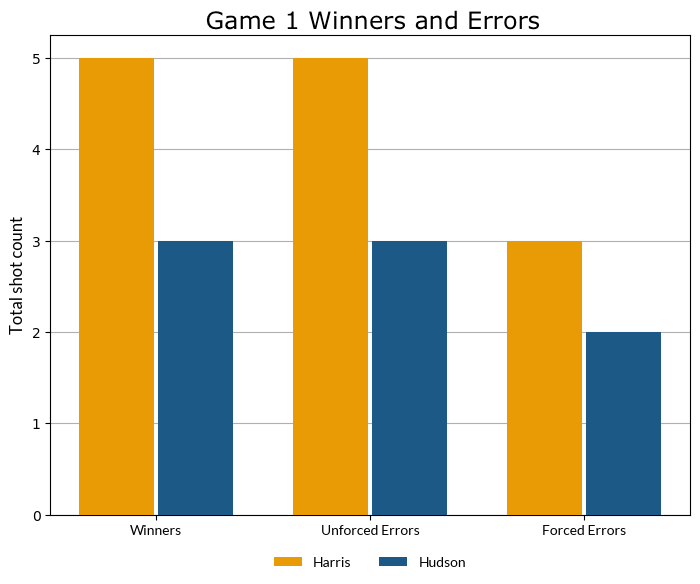

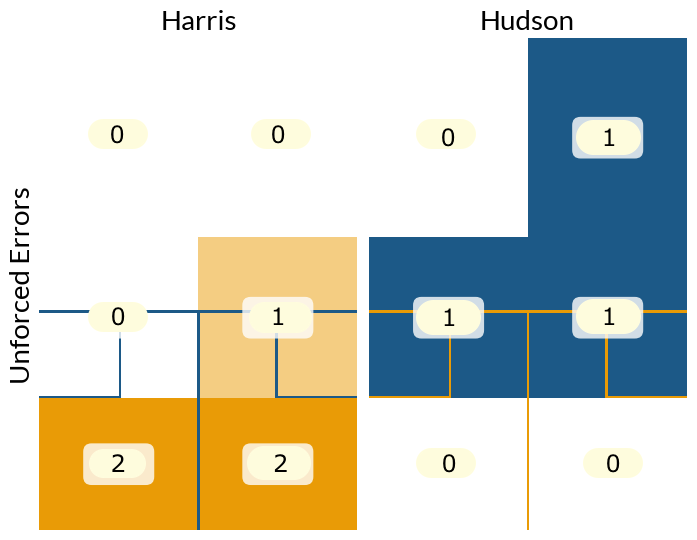

In Game 1, Harris (5) hit more Winners than Hudson (3). Accompanying these Winners, Harris also committed five Unforced Errors to Hudson’s three. A higher number of both Winners and Unforced Errors often points to a more proactive style of squash, indicative of a player looking to dictate play, accepting the risks of stretching the margins above the tin along with the rewards such strokeplay can offer. The margins went against Harris here: despite opening up a 9-6 lead and having Game ball at 10-9, it was Hudson who took a close-run opening Game 12-10.

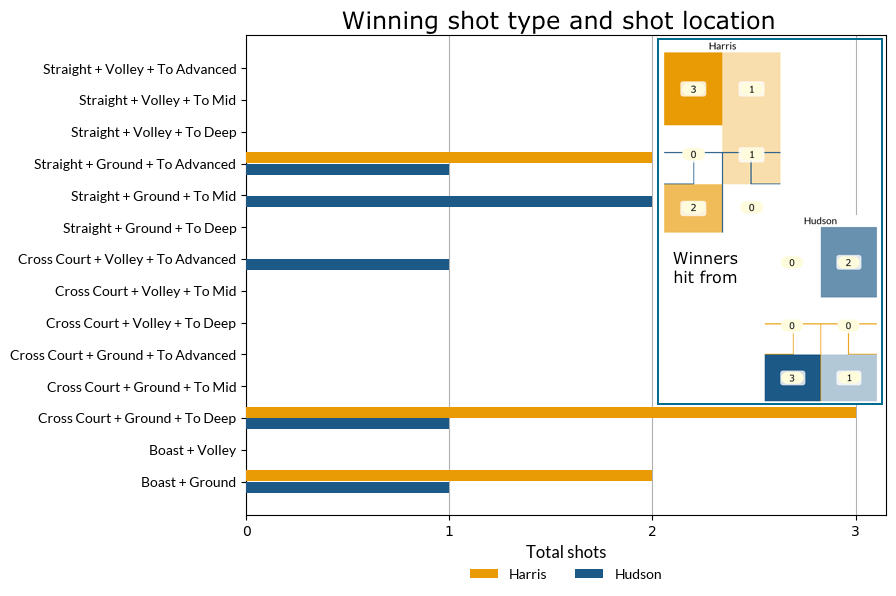

A look at what kind of Winners and Unforced Errors the players hit is also revealing: all seven of Harris’ Winning shots (Outright Winners and Hudson’s Forced Errors) were hit to advanced or deep regions of the court, and all but one was hit from advanced or deep regions too.

One conclusion we can draw from this stat is that Harris stretched the play well, applying pressure to Hudson by using the extremities of the court. Viewers will indeed recall several immaculate lengths to deep and short drops to the front right corner.

But stretching the play is dangerous if attempted from risky positions. As we’ve seen, despite his high Winner count, Harris committed as many Unforced Errors. A nod to Harris’ proactive play, he committed 4 of his 5 Unforced Errors from deep regions on the court. Hudson, by contrast, made not a single Unforced Error from behind the service boxes. Were we in Harris’ corner between games, we would encourage his make-things-happen approach, but note that aggressive shots from low-percentage positions had cost him badly.

Harris’ high error rate from the back hints at another important element in this contest: the benefits of hitting good length. As we saw in the first performance metrics chart above, Harris (43%) and Hudson (45%) played a similar number of shots from deep regions. A more significant gap emerges, however, when considering shots from deep set against who won the point.

As can be seen in the charts below, regardless of who won the point, Hudson consistently hit 42-44% of shots from deep. Harris’ success, by contrast, was strongly correlated with his court position: in those points he won, Harris hit just 37% of shots from deep; this number rises sharply to 50% of shots hit from deep on points he lost.

Combined with knowledge that Harris committed 4 Unforced Errors from deep, these stats point to a clear pattern of success for Hudson: keep Harris deep and trust that the error will come. Were we in Hudson’s camp between games, our message would have been simple: keep hammering those lengths.

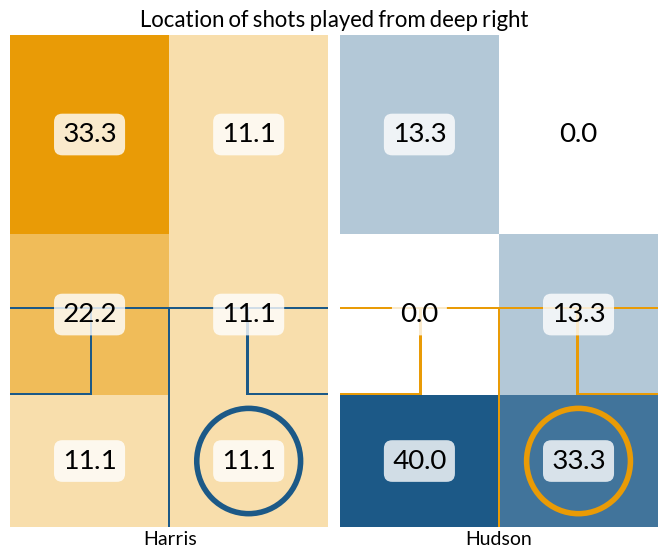

Once hitting from deep, the players’ shot selection varied substantially. From deep on the backhand, Harris hit 1 in 4 shots to the front; Hudson only elected to take it short from this region every eight shots. This difference is even starker in shots from deep on the forehand: as seen in the charts below, Harris hit almost half of his shots from the back right to short (44.4%), while Hudson hit three-quarters (73.3%) of his shots back to deep positions.

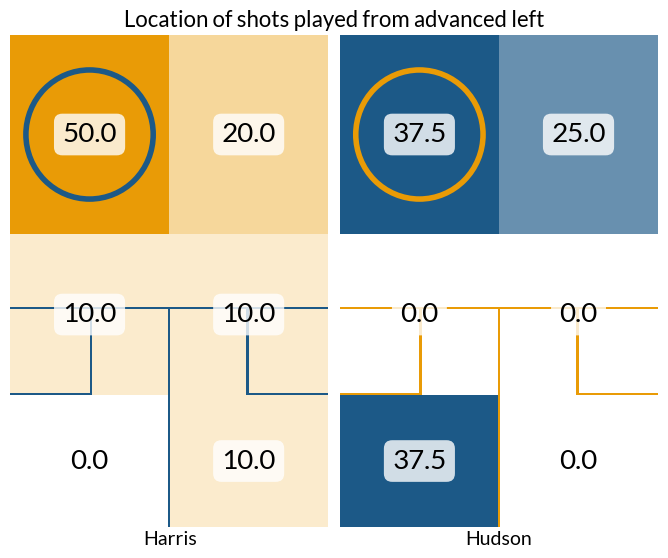

Once in the front left, it is noteworthy how Harris opted to keep play in the front corners. Of the 10 shots he hit from advanced on the backhand, Harris returned the ball to the front left on 5 occasions and kept the ball short 7. The figures in the chart below represent the percentage of shots played.

Yet, despite Harris’ keenness to test Hudson short on the backhand from both deep and advanced locations, his shots to the front left from mid-court are conspicuous in their absence: of the 43 shots Harris hit from mid-court in Game 1, he took the ball short on Hudson’s backhand on just one occasion. Were we in Harris’ corner, we might advise reducing the tin-flirting from deep, and replacing these shots with drops from the less risky midcourt.

As noted by the commentary team, late into Game 1 Hudson appeared to be feeling the effects of some lengthy exchanges. As is so often the case, the impact of bruising rallies is not seen on the scoreboard until deeper into the match. The same is true statistically. Hudson in fact won the three longest rallies in Game 1, and two of the three points immediately following these exchanges – so often the endurance player’s reward.

If Harris’s game plan was to extend the rallies and back himself physically, this may have been reflected in the number of times the players opted to slow the tempo of the rally – such as with lobs from the front or lofted drives from the back. Harris took the pace off every six shots, while Hudson did so only once every twelve.

Harris narrowly lost the opening Game, but this approach may have paid off in the end: he eventually claimed the tie 3-1. And if his game plan was indeed to test Hudson physically, all the more reason to cut out the Unforced Errors from deep.

For more stats, blogs, and information about how you can use Cross Court Analytics’ match report service, check out their website, Twitter or Facebook.